Collection

AboutHow the Peso Was Born — Uruguay’s Hidden Masterpieces of Money

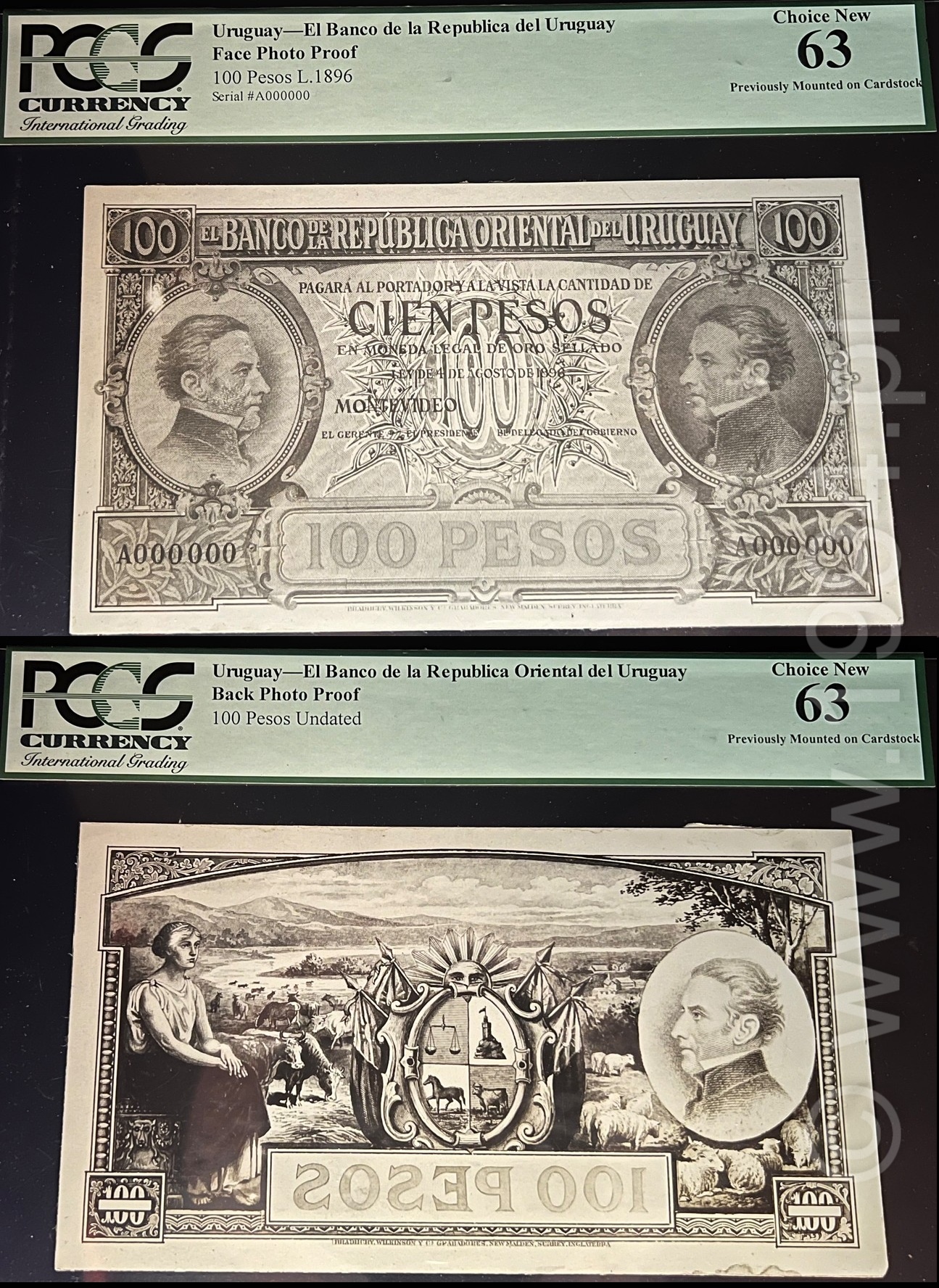

What did Uruguay’s money look like before it was money? Not the notes we’ve all seen — the one-of-a-kind photographic proofs and engraved portraits that shaped them. This is the story of how a country found its face: through New York’s American Bank Note Company, London’s Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co., and a design language that had to convince dockworkers in Montevideo and bankers in London at the same time.

The six pairs below aren’t collectibles made for show. They’re working tools: large, razor-sharp photographs taken from the master dies before plates were hardened. In black-and-white, engravers checked line weight, lettering, and symmetry; in warm sepia, bank directors previewed how the finished note might feel on the desk. Most were tossed when contracts ended. These survived.

The six that tell the story

Click any thumbnail to enlarge. Titles link to the detailed JSON item pages.

The face behind the faces

A final piece ties the whole arc together: a Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co. master portrait of Artigas — a true engraved die proof on India paper, stamped “Cancelled.” Think of it as the studio headshot every later note could borrow. It is calmer than ABNC’s heroic portraits and shows how London leaned toward photographic realism in the 1910s–1920s.

How photographic proofs were made (and why they’re rare)

First came the engraving — lines cut into a steel die under a glass. From that die, ABNC produced large, high-contrast photographs on sensitized paper. In black-and-white, engravers and letterers marked corrections; in sepia, executives judged balance and tone. Only when these passed did plates get hardened for real printing. Proof albums stayed inside the printer. Decades later, when archives were cleaned, most were destroyed. The few we have today are the lucky survivors.

What changed between 1896 and 1935

The 1896 reform gave Uruguay a stable peso and a confident look: heroic portraits, deep guilloches, busy frames that shouted security. By 1935, tastes and technology had shifted. The layouts grew cleaner, allegory turned monumental, and the engraving grid adapted to faster intaglio presses. Same message — trust us — delivered with fewer flourishes and more steel-line discipline.

Looking ahead: the 1939 specimen era

By the decade’s end, this vocabulary — portraits, arms, ports, and fields of tight line work — matured into a fully standardized specimen program. Our next Spotlight follows that leap in 1939, where every denomination appears in a unified format with explicit SPECIMEN controls. When that piece goes live, you’ll find it here: Uruguay 1939 — The Standardized Specimen Program.