Collection

About

“Signed to Say Thank You” — Colby, Kansas 1902–1929–1944

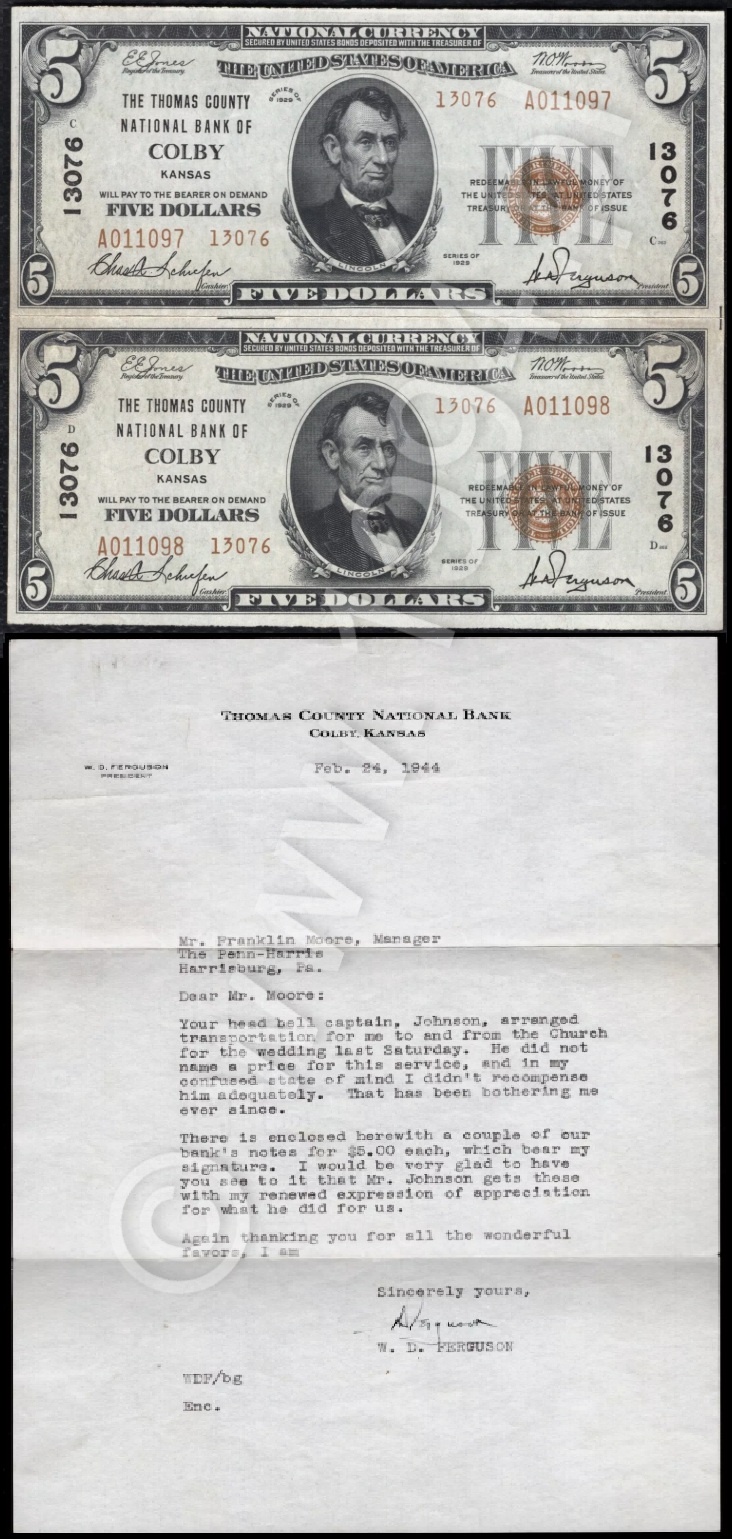

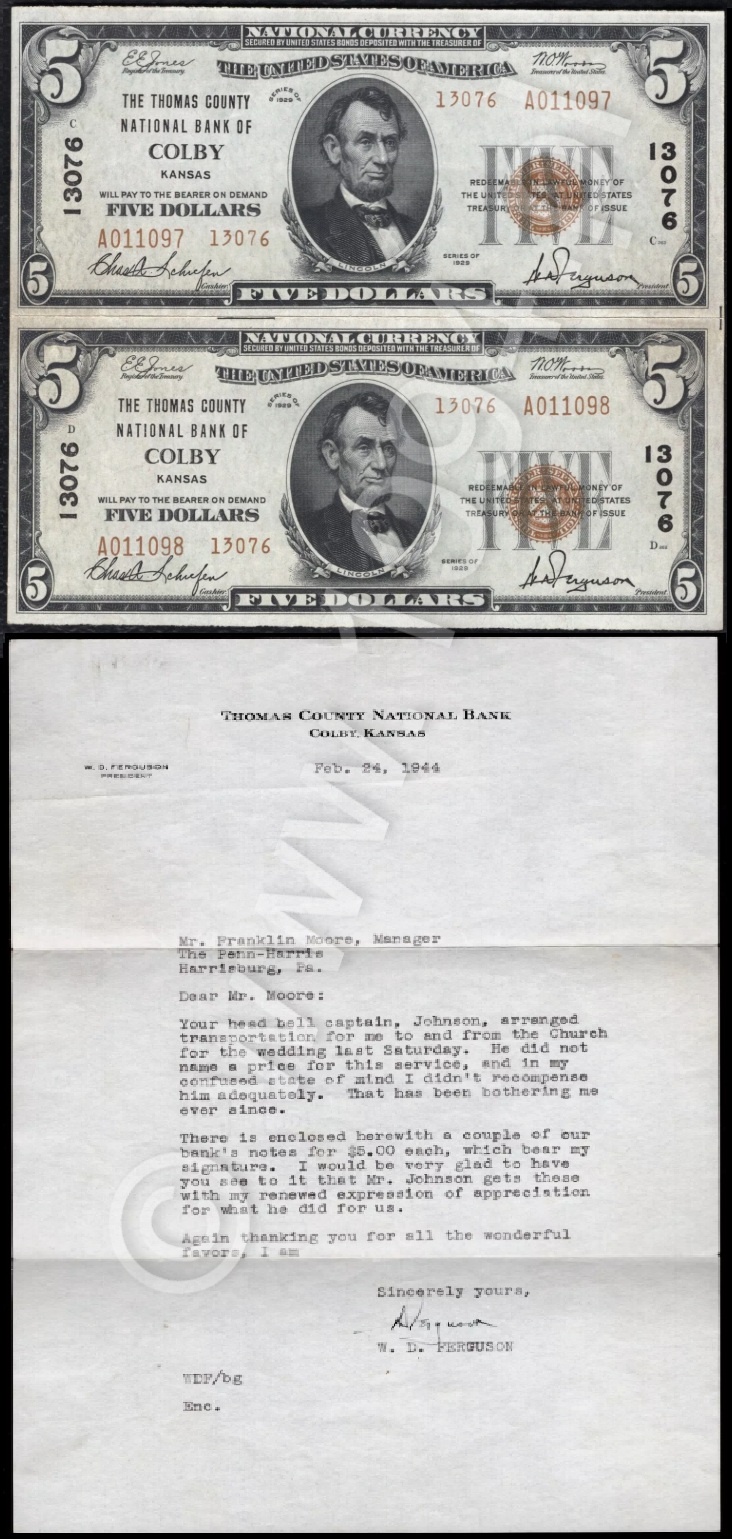

Some banks leave ledgers. This one left paper—three survivors that can still be held: an early 1902 $5 Plain Back, a hard‑worked 1929 $5 Type 1, and an uncut, consecutive pair of 1929 $5 notes accompanied by a 1944 letter on official letterhead. All three are tied to one name: W. D. Ferguson, President of The Thomas County National Bank of Colby, Kansas (Charter 13076).

The bank was organized on May 5, 1927 and chartered a week later on May 12, 1927. Its officers bridge the entire story: cashier N. Reimers (1927–1930) then C. A. Schiefen (1931–1935), with W. D. Ferguson as president throughout. By the numbers the bank was modest (resources rising from $663,449 in 1927 to a 1930 peak just over $1,034,699; circulation hovering near $50,000), yet its paper output—large and small size—captures the end of the National Banking era in one prairie town.

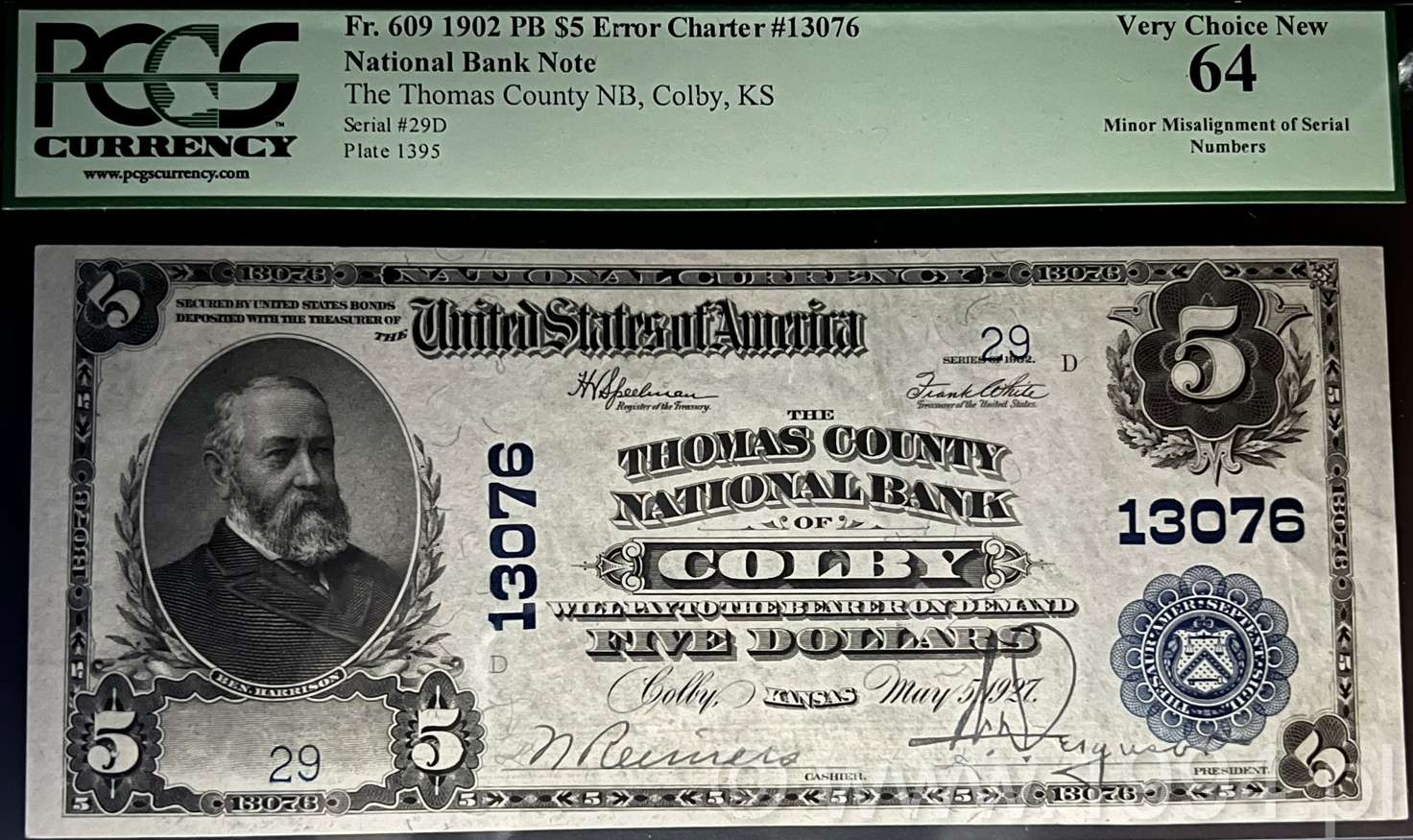

I. 1902: A bank is born, and the first signature is ink

The 1902 $5 Plain Back (Fr. 609) is the bank’s opening statement: Benjamin Harrison engraved at left, blue charter numerals, and hand‑signed officer names. Its early Serial 29‑D and plate data anchor the note to the bank’s inaugural year. A minor serial misalignment gives it personality—rare on Nationals, whose overprints were closely policed.

For our story, the key detail is not the error; it’s the signature line: W. D. Ferguson, President. This is ink—an officer literally writing the bank’s promise onto the money.

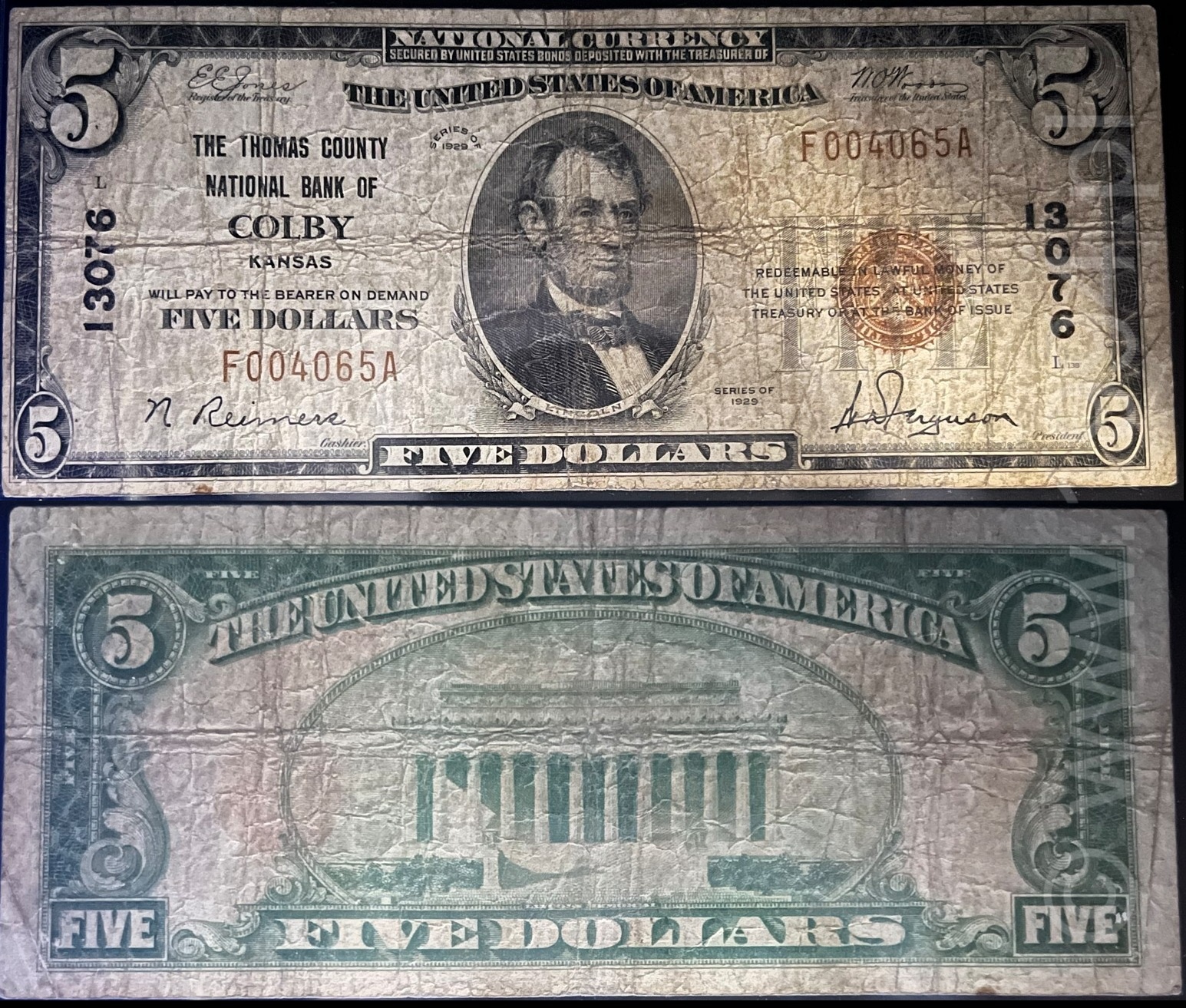

II. 1929: The small‑size “work note” that proves circulation

When Nationals were resized in 1929, Colby’s issues adopted the new standardized face with Abraham Lincoln at center, a brown Treasury seal, and printed facsimiles of the same two names: N. Reimers, Cashier, and W. D. Ferguson, President. The circulated note shown here (serial F004065A) is honest—creased, handled, but fully legible. It is the everyday part of the story: Colby’s notes were not just printed; they were used.

III. 1944: The letter that turns paper into provenance

On February 24, 1944—nearly two decades after issue—President W. D. Ferguson typed a letter on bank stationery to hotel manager Mr. Franklin Moore in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania. He explains that the hotel’s head bell captain, Johnson, arranged transportation to and from a church for a wedding the prior Saturday, refused any payment, and that this had bothered him. As a thank‑you, he encloses “a couple of our bank’s notes for $5.00 each, which bear my signature,” asking that Mr. Moore pass them to Johnson with Ferguson’s renewed appreciation. Then—one more time—he signs: W. D. Ferguson.

Those enclosed notes survive today exactly as he sent them: an uncut consecutive pair, serials A011097 and A011098. The letter is not a caption; it is the act that created this provenance. It proves that Colby’s Nationals remained in bank drawers into the 1940s and that the president himself gifted them, explicitly because they “bear my signature.”

IV. One name across three decades

Read in order, the artifacts show the same name in three media: ink (1902 hand‑signed large size), plate (1929 printed facsimiles on small size), and ink again (the 1944 letter). The continuity matters. Most banks changed officers frequently; Colby’s president did not. Ferguson’s name becomes a constant that ties the bank’s 1902 launch to its Depression‑era circulation and to a moment of personal gratitude in 1944.

V. Why this matters beyond one town

Collectors chase condition, populations, and varieties. Provenance is rarer. The uncut pair with the letter is documentary: it tells you not just what the notes are, but how they left the bank and why they were kept. Paired with the 1902 Plain Back (the bank’s first form factor and first Ferguson signature) and a real‑world 1929 survivor (proof of actual use), the set reads like a single ledger entry: issued, circulated, preserved, and finally—signed to say thank you.

Early serial 29‑D; engraved portrait of Benjamin Harrison; first appearance of Ferguson’s hand‑signed name.

A working survivor with the same printed officer names (Reimers & Ferguson) that linked small‑town commerce to national finance.

Two uncut notes accompanied by Ferguson’s hand‑signed letter of gratitude — a unique union of paper money and personal history.