Collection

Educational overview of three pre-Federation Australian specimens

The pre-Federation era in Australia produced some of the most distinctive private banknotes of the British colonial world. Before 1910, individual banks issued their own paper money under state charters, a system that mirrored Scotland’s model but operated under the practical realities of a continent still forming its national identity. Each bank relied on established London printers—Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co., or Skipper & East, for example—to design, engrave, and supply currency that would both circulate locally and project credibility to an emerging economy.

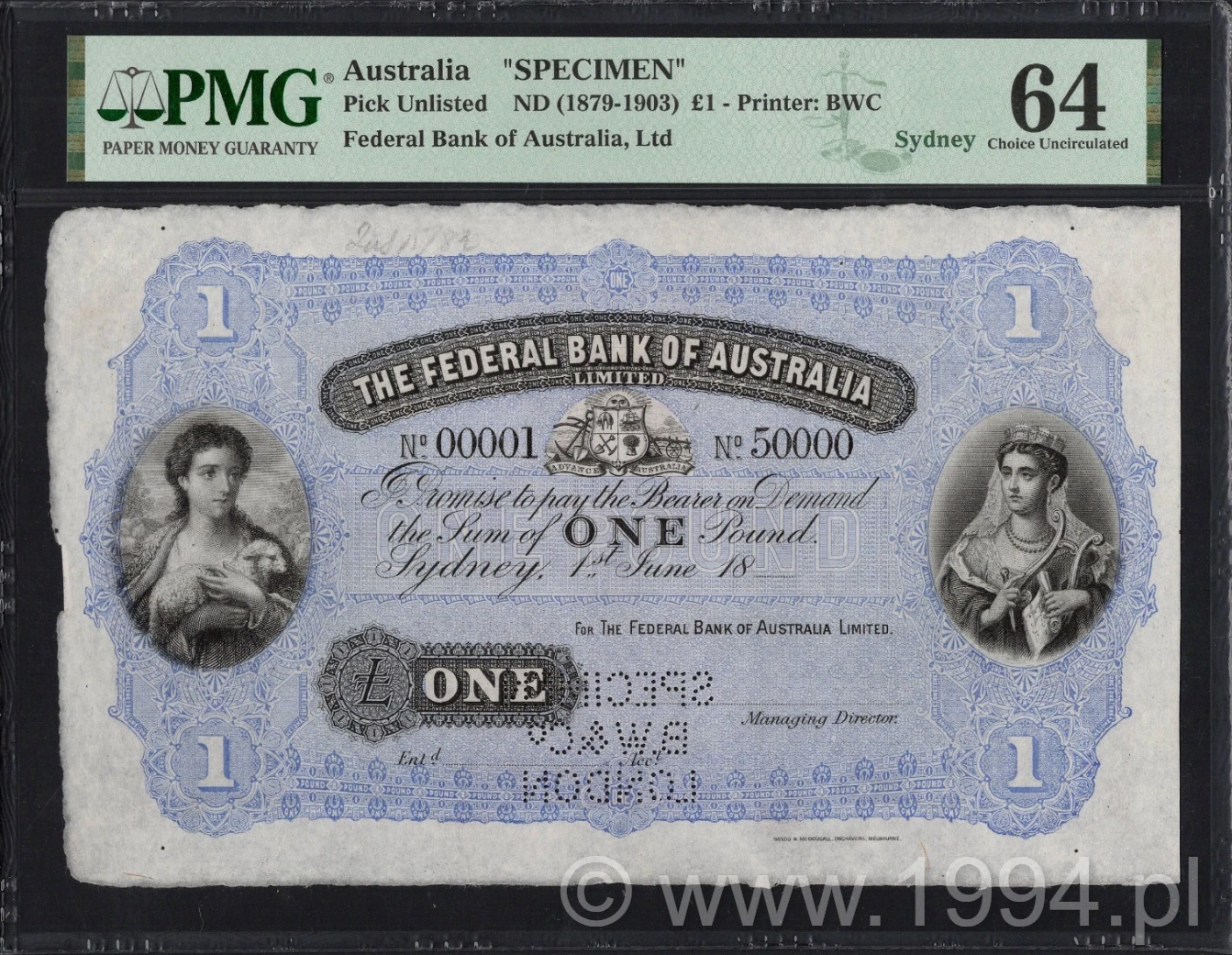

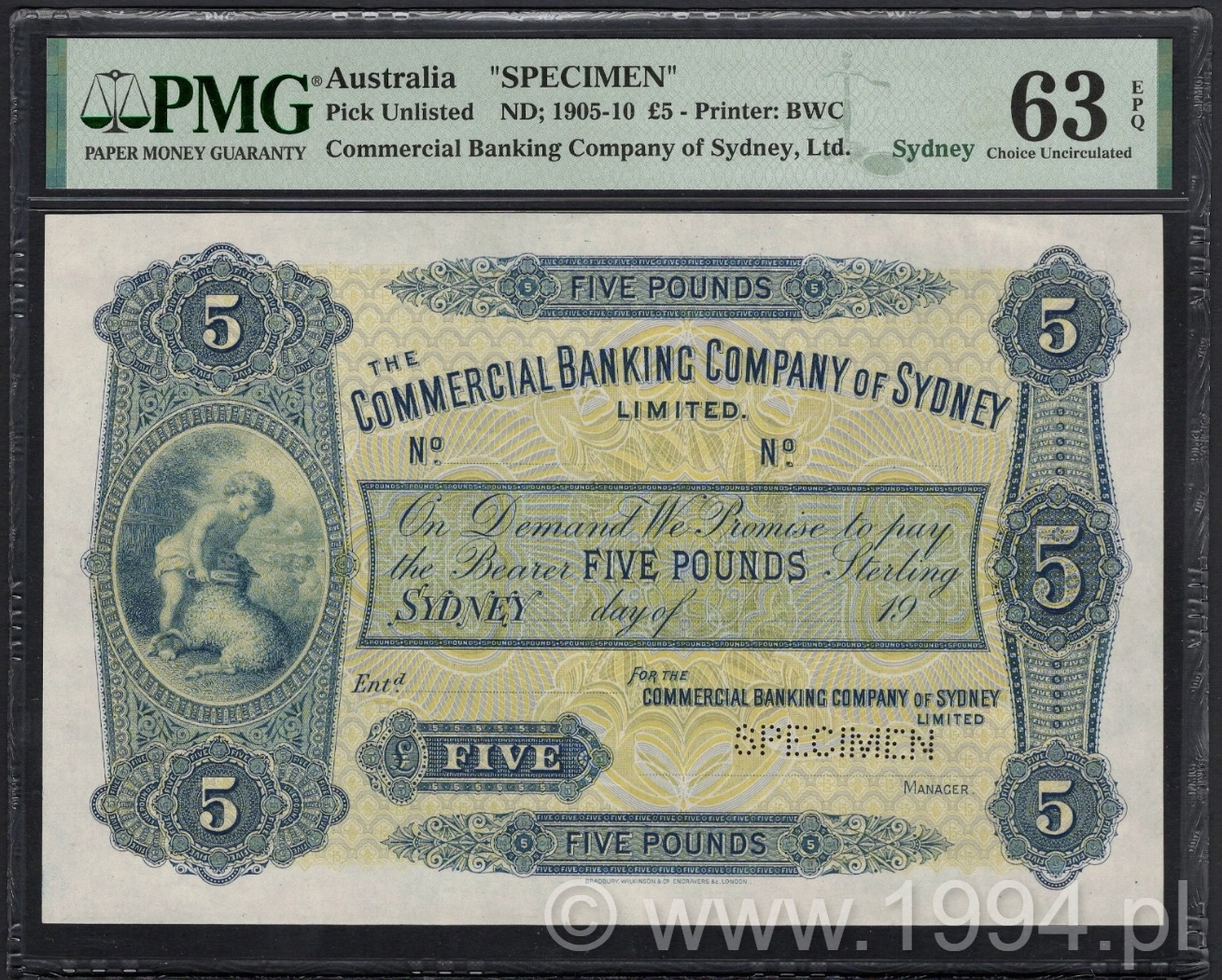

The three examples shown here—the Commercial Bank of Australia £100, the Federal Bank of Australia £1, and the Commercial Banking Company of Sydney £5—represent the final generation of privately issued notes before national consolidation under the 1910 Australian Notes Act. Together, they highlight both the artistry and the logistical sophistication behind a decentralized paper-money system that nonetheless achieved remarkable trust and stability for its time.

Why were specimens made at all? In the 19th century, every new note design required official approval—first by the bank’s directors, then by colonial auditors or government observers. Printers produced specimen proofs to demonstrate engraving quality and layout, and these were kept in secure reference files or distributed to correspondents as record copies. Specimens ensured that future print orders matched the approved plate and that forgeries could be compared against an official model.

Why are surviving specimens so rare? In theory, every proof and specimen should have been destroyed when the printer’s contract ended. Many were indeed pulped during the centralization of 1910–1911, when private issues were recalled and replaced by Commonwealth notes. The few that remain often owe their survival to printer archives, employee keepsakes, or inter-bank exchanges where a specimen might have been filed as a legitimate reference sample. Their presence today bridges two worlds: one of private trust and another of national control.

Why the design consistency? Despite being separate institutions, these banks all used London engravers who reused symbolic elements—the seated Britannia, allegorical maidens, and classical borders—to project imperial authority. Local flavor was minimal. Australia’s distance from Britain made design changes slow, and so, by necessity, the imagery stayed conservative. This is why so many late colonial notes still resemble Victorian securities rather than distinctly Australian art.

What changed after 1910? The Australian Notes Act transferred the right of issue to the Commonwealth Treasury, effectively ending 60 years of private currency. Banks lost their note-issuing privilege but gained reliability as deposit institutions. Within two years, the Commonwealth Bank and later the Reserve Bank absorbed all production and redemption functions. The earlier printer proofs—once mere office samples—suddenly became historical evidence of a closed era.

These three specimens illustrate more than design—they record a transitional philosophy of money itself. Each note embodies a step from personal credit (a bank’s promise) toward collective trust (a nation’s guarantee). That shift—visible in every watermark, signature, and engraved Britannia—marks the birth of Australia’s unified currency identity.