Australia’s early paper money emerged not from a centralized government, but from necessity. In the early 19th century, the vast distance from Britain and a shortage of coin forced local institutions to improvise. Promissory notes, handwritten drafts, and the so-called “rum currency” circulated freely long before formal banks appeared. The Bank of New South Wales, founded in 1817, became the first authorized issuer of printed notes, setting a precedent for dozens of private and colonial banks that followed across the continent.

Through the mid-1800s, each colony—New South Wales, Victoria, Queensland, South Australia, Western Australia, and Tasmania—licensed its own banks to issue notes redeemable in gold or sterling. This “free banking” system created a diverse and colorful array of designs, often printed in London or New York to ensure quality and deterrence against forgery. Engravers such as Bradbury, Wilkinson & Co., Perkins, Bacon & Petch, and the American Bank Note Company produced engravings of extraordinary complexity, featuring allegorical figures, native fauna, and maritime scenes that reflected the colonies’ growing confidence and wealth from gold, wool, and trade.

Yet the system was also fragile. Periodic bank runs and the 1893 financial crisis exposed the risks of uncoordinated note issuance. Many institutions failed or merged, paving the way for federation and a call for national monetary control. When the Commonwealth of Australia was established in 1901, it inherited six separate banking traditions—and a public wary of instability. The Australian Notes Act of 1910 finally prohibited private banks from issuing currency, transferring the power to the new Commonwealth Treasury and, soon after, to the Commonwealth Bank of Australia.

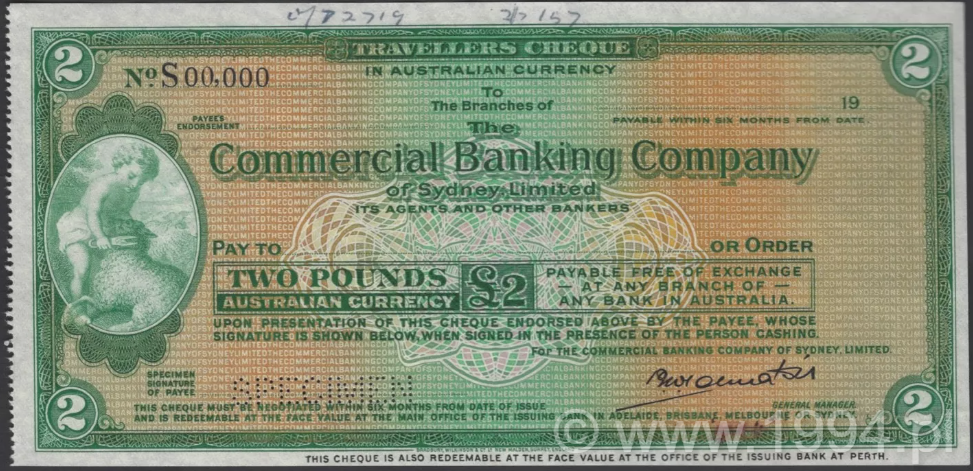

The transition period from the 1880s to the early 1910s was one of technical brilliance and artistic maturity. Specimen proofs and archival pulls from this era—produced in tiny numbers for design approval—document the last flowering of Australia’s private note engraving tradition. Among the finest are the Federal Bank of Australia 1 Pound specimen (annotated, PMG 64), a remnant of a bank undone by the 1893 collapse; the Commercial Bank of Sydney 5 Pounds proof (circa 1905–10, PMG 63 EPQ), whose elaborate guilloche and British-Empire iconography embody colonial prosperity; and the monumental Commercial Bank of Australia £100 specimen (1880–1910, PMG 64), engraved in London and printed in Melbourne—a final synthesis of local industry and imported craftsmanship.

Together, these notes illuminate more than banking—they chart the evolution of identity. They reveal how Australia’s early banks acted as both financiers and ambassadors, broadcasting the nation’s economic strength and aesthetic ideals to a global audience. To study these specimens is to trace Australia’s journey from scattered colonial outposts to a unified Commonwealth, told through ink, paper, and the unspoken promise printed across every note: trust.